Pomo frenzy

In his book Modernity Under Siege, Argentine sociologist J.J. Sebreli points out that according to postmodernistic criteria, we should view the Copernican Revolution as a local phenomenon restricted to Central Europe during the late XVI century, since Copernicus was a Polish priest who advanced his theory in a booklet called De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On The Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) in 1543. Therefore, the double-spin planetary movement around themselves and about the Sun ought to be held true only for sixteenth century Central Europe. This implies it has ceased to be true, an assertion that plainly contradicts the fact that after 450 years we still believe in the heliocentric planetary system as developed by Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo. Such is the boundless frenzy postmodernist are possessed by in their blind spell to attack anything that has to do with reason, reality and science. However, I would like to point out that, as far as the history of science is concerned, certainty as to the origins and intentions of the purported "discoverers" of certain crucial theories is far from clear. My thesis in this essay advances the notion that neither Copernicus nor Bowlby held the smallest intention of revolutionizing the scientific status quo in their respective disciplines. All they wanted was to offer a more rational explanation of otherwise untenable theories: the Ptolemaic System and Freudian Psychoanalysis.

COPERNICUS

Nicolaus Copernicus was a redoubtable catholic priest learned in Arts, Medicine, Laws, especially canonical laws, Theology and Philosophy, all disciplines in which he excelled. He made a poor astronomer, though. He held religious rather than scientific reasons to concoct his heliocentric planetary system. He had gathered no empirical evidence to buttress the theory he advanced. According to Alexadre Koyré he had observed the skies only 27 times during his lifetime.

The universe, the cosmos, resulted from a sacred act of God's creation. Therefore, what we observe when we scrutinize the skies are reflections of God's work. God could not have created such an ugly imperfection as the Ptolemaic system suggested. God was perfect, and perfection was at the time thought to be an ideal clockwork system, perfectly round, absolute, and without yearly corrections. Copernicus's system fit these principles of perfection conveniently. The planets, each set on a solid sphere which revolved round the sun constituted perfect harmony. That was why his system was far from rejected from the Papacy. Pope Paul III was a Copernican convert and used his "discovery" as a counter-reformation weapon. So, summing up, Copernicus did not advance his theory of planetary movement as a tribute to facts, science and truth, but as a tribute to God Almighty.

Let's not forget Copernicus lived in the XVI century, the century of the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation. Catholics had to sharpen their wits to show they were the devotest congregation to honour God, that God was served in his omnipotent perfection.

Only when Paul III (Copernicus' s pope) became pope in 1534 did the church receive the leadership it needed to orchestrate these impulses toward reform and to meet the challenge of the protestants.

One of Paul's most important initiatives was to nominate sincere reformers such as Gasparo Contarini and Reginald Pole to the College of Cardinals. He also gave encouragement to new religious orders such as the Theatines, Capuchins, Ursulines, and especially the Jesuits. This last group, under the leadership of St. Ignatius Loyola, consisted of highly educated men dedicated to a renewal of piety through preaching, catechetical instruction, and the use of Loyola's Spiritual Exercises for retreats. Perhaps Paul's most dramatic action was the convocation of the Council of Trent in 1545 to deal with the doctrinal and disciplinary questions raised by the Protestants. Often working in an uneasy alliance with the Holy Roman emperor Charles V, Paul, like many of his successors, did not hesitate to use both diplomatic and military measures against the Protestants.

Let's now take a closer look at Copernicus's biographical facts.

Copernicus was born on February 19, 1473, in Thorn (now Torun), Poland, to a family of merchants and municipal officials. Copernicus's maternal uncle, Bishop Lukasz Watzenrode, saw to it that his nephew obtained a solid education at the best universities. Copernicus entered Jagiellonian University in 1491, studied the liberal arts for four years without receiving a degree, and then, like many Poles of his social class, went to Italy to study medicine and law. Before he left, his uncle had him appointed a church administrator in Frauenberg (now Frombork); this was a post with financial responsibilities but no priestly duties. In January 1497 Copernicus began to study canon law at the University of Bologna while living in the home of a mathematics professor, Domenico Maria de Novara, who first stimulated somewhat dreamy Copernicus to take an interest in geography and astronomy, was an early critic of the accuracy of the Geography of the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy. He taught Copernicus the very basics of astronomy, such as the use of the telescope, to observe the skies (for example, he knew that on the 9th of March, 1497 an eclipse was bound to occur and surprised young Nico by showing him how the star Aldebaran disappeared behind a shadow cast by the moon). So Nicolaus became his math professor's astronomy apprentice for about 3 years.

However, his vocation as an astronomer proved feeble: In 1500 Copernicus gained permission to study medicine at Padua, the university where Galileo taught nearly a century later. It was not unusual at the time to study a subject at one university and then to receive a degree from another -often less expensive- institution. And so Copernicus, without completing his medical studies, received a doctorate in canon law from Ferrara in 1503 and then returned to Poland to take up his administrative duties.

From 1503 to 1510, Copernicus lived in his uncle's bishopric palace in Lidzbark Warminski, assisting in the administration of the diocese and in the conflict against the Teutonic Knights. There he published his first book, a Latin translation of letters on morals by a 7th-century Byzantine writer, Theophylactus of Simocatta. Sometime between 1507 and 1515, he completed a short astronomical draft essay, De Hypothesibus Motuum Coelestium a se Constitutis Commentariolus (known as The Commentariolus), which was not published until the 19th century. In this booklet he laid down the principles Domenico Maria de Novara had taught him about a heliocentric planetary system. He distributed it among his acquaintances and pupils and asked them to write down any comments they may have. When they were done commenting on his planetary system they would turn the commented booklet back for Copernicus to gather an assessment of how the heliocentric system impressed his readers, (hence its name: Commentariolus).

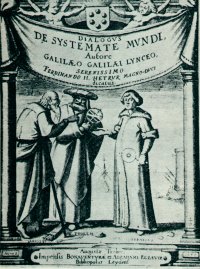

After moving to Frauenburg in 1512, Copernicus took part in the Fifth Lateran Council's commission on calendar reform in 1515; wrote a treatise on money in 1517; but it was not until 1530 that he seriously began working on De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), which was finished by a pupil of his, who was eager to see the work in print. It eventually appeared a first publication by a Lutheran printer in Nuremberg, Germany, just before Copernicus's death in 1543.

The cosmology that was eventually replaced by Copernican theory postulated a geocentric universe in which the earth was stationary and motionless at the center of several concentric, rotating spheres. These spheres bore (in order from the earth outward) the following celestial bodies: the moon, Mercury, Venus, the sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. The finite outermost sphere bore the so-called fixed stars. (This last sphere was said to wobble slowly, thereby producing the precession of the equinoxes)

One phenomenon had posed a particular problem for cosmologists and natural philosophers since ancient times: the apparent retrograde (backward) motion of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. From time to time the daily motion of these planets through the sky appears to halt and then to proceed in the opposite direction. In an attempt to account for this retrograde motion, medieval cosmology stated that each planet revolved on the edge of a circle called the epicycle, and the center of each epicycle revolved around the earth on a path called the deferent.

The Copernican System and Its Influence

The major premises of Copernicus's theory are that the earth rotates daily on its axis and revolves yearly around the sun. He argued, furthermore, that the planets also circle the sun, and that the earth precesses on its axis (wobbles like a top) as it rotates. The Copernican theory retained many features of the cosmology it replaced, including the solid, planet-bearing spheres, the sun as a source of light, but not a heavenly body -let alone to think of it as a star- and the finite outermost sphere bearing the fixed stars. On the other hand, Copernicus's heliocentric theories of planetary motion had the advantage of accounting for the apparent daily and yearly motion of the sun and stars, and it neatly explained the apparent retrograde motion of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn and the fact that Mercury and Venus never move more than a certain distance from the sun. Copernicus's theory also stated that the sphere of the fixed stars was stationary.

Another important feature of Copernican theory is that it allowed a new ordering of the planets according to their periods of revolution. In Copernicus's universe, unlike Ptolemy's, the greater the radius of a planet's orbit, the greater the time the planet takes to make one circuit around the sun. But the price of accepting the concept of a moving earth was too high for most 16th-century readers who understood Copernicus's claims. In addition, Copernicus's calculations of astronomical positions were neither decisively simpler nor more accurate than those of his predecessors, even though his heliocentric theory made good physical sense, for the first time, of planetary movements. As a result, parts of his theory were adopted, while the radical core was ignored or rejected.

There were but ten Copernicans between 1543 and 1600. Most worked outside the universities in princely, royal, or imperial courts; the most famous were Galileo and the German astronomer Johannes Kepler. These men often differed in their reasons for supporting the Copernican system. In 1588 an important middle position was developed by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in which the earth remained at rest and all the planets revolved around the sun as it revolved around the earth.

After the suppression of Copernican theory occasioned by the ecclesiastical trial of Galileo in 1633, some Jesuit philosophers remained secret followers of Copernicus. Many others adopted the geocentric-heliocentric system of Brahe. By the late 17th century and the rise of the system of celestial mechanics propounded by the English natural philosopher Sir Isaac Newton, most major thinkers in England, France, the Netherlands, and Denmark were Copernicans. Natural philosophers in the other European countries, however, held strong anti-Copernican views for at least another century.

It scratches one's imagination to think how by the mid-fifties, when

irrationalist trends felt at the peak of their triumph in Europe and

the United States, and their voice the only one that sounded loud

and clear among intellectual circles worldwide on any imaginable

issue, be it art, politics, economics, the social sciences, music, the

media, and so on, when true professional charlatans of the calibre

of Foucault, Lacan, Melanie Klein, Levi-Strauss, Spengler kept,

and still keep, the upper hand among the intelligentsia, a lone

British psychoanalyst would leap into the arena and declare war

on the long-standing myths pestering psychological thinking ever

since Freud, brandishing the then already ragged banner of

scientificism. It must have struck a dissonant chord in own

Bowlby's brains or thereabouts for he decided, as a matter of

sheer fact, to brandish the science banner on one hand and

Freud's object-relations theory on the other.

As we will show, albeit the redoubtable importance of Bowlby's

work, inner theoretical contradictions and heavy compromises

with psychoanalytic theory make the whole far from a monolithic,

coherent, work, weaken its very bases, and, more importantly,

determine a sterile fate and preclude any hope for progress to

those entering the Attachment Theory field of enquiry.

For instance, his compromise with psychoanalysis forced him to

assert his was an object-relations theory thus pushing him to add

and heavily rely on a more than controversial argument: the

Working Models theory, a natural corollary of an inner

representational model, both totally unrefutable arguments and

hence uninteresting for the scientific community. We will

demonstrate how both issues: object-relations theory and

working-models theory fill attachment theory as a whole with

hosts of conceptual and logical contradictions, which we feel must

be underscored, so as not to identify John Bowlby with a god-like

figure, on the one hand; and on the other to display how current

attachment theory and research, particularly in the United States,

connives with, and thrives on, this spurious, dispensable parts of

attachment theory.

BOWLBY'S SCIENTIFIC STANCE

Bowlby's first attempts focused on countering psychoanalysis

psychologism and replacing it by a more common-sense,

everyday experiences both children and their parents undergo,

and which may be labelled "environmentalism", which enable him

to make a strong point against psychoanalysis' subjectivism,

fantasies, inner representational world, and the like, since the

hypotheses he advanced were in keeping with empirical data,

whereas, psychoanalytic introspective speculation was not liable

to contrastability, and so it simply rendered it unscientific.

Let's recall the three fundamental papers that, to my mind, make a

tremendous dent in psychoanalysis' structure:

Bowlby's first formal statement of Attachment Theory,

drawing heavily on ethological concepts, was presented in

London in three now classic papers read to the British

Psychoanalytic Society. The first, The Nature of the

Child's Tie to his Mother was presented in 1957 where he

reviews the current psychoanalytic explanations for the

child's libidinal tie to the mother (in short, the theories of

secondary drive, primary object sucking, primary object

clinging, and primary return to womb craving). This paper

raised quite a storm at the Psychoanalytic Society. Even

Bowlby's own analyst, Joan Riviere protested and Donald

Winnicott wrote to thank her: "It was certainly a difficult paper

to appreciate without giving away everything that

has been fought for by Freud". Anna Freud, who missed the

meeting but read the paper, wrote: "Dr Bowlby is too

valuable a person to get lost to psychoanalysis".

The next paper in the series, Separation Anxiety, was

presented in 1959. In this paper, Bowlby pointed out that

traditional theory fails to explain both the intense attachment

to mother figure and young children's dramatic responses to

separation. Robertson and Bowlby had identified three

phases of separation response:

1. Protest (related to separation anxiety)

2. Despair (related to grief and mourning), and

3. Detachment or denial (related to defence).

All of which proved Bowlby's crucial point: separation anxiety

is experienced when attachment behaviour is activated and

cannot be terminated unless reunion is restored.

Unlike other analysts, Bowlby advanced the view that

excessive separation anxiety is usually caused by adverse

family experiences, such as repeated threats of

abandonment or rejections by parents, or to parent's or

siblings' illnesses or death for which the child feels

responsible.

In the third major theoretical paper, Grief and Mourning in

Infancy and Early Childhood, read to the Psychoanalytic

Society in 1959 (published in 1960),

Bowlby questioned the then prevailing view that infantile

narcissism is an obstacle to the experience of grief upon loss

of a love object. He disputed Anna Freud's contention that

infants cannot mourn, because of insufficient ego

development, and hence experience nothing more than brief

bouts of separation anxiety provided a satisfactory substitute

is available. He also questioned Melanie Klein's claim that

loss of the breast at weaning is the greatest loss in infancy.

Instead, he advanced the view that grief and mourning

appear whenever attachment behaviours are activated but

the mother continues to be unavailable.

As with the first paper, many members of the British

Psychoanalytic Society voiced strong disagreement. Donald

Winnicott wrote to Anna Freud: "I can't quite make out why it

is that Bowlby's papers are building up in me a kind of

revulsion although in fact he has been scrupulously fair to

me in my writings". Because he was undermining the very

bases of psychologism in psychoanalysis.

These three papers were more than enough to tear the fantasy

building of speculative psychoanalysis to pieces. So why did

Bowlby have to concede his was an object-relations theory, when

it sprang from the very reading of the papers that it was a theory

about personal relationships. We insist in this distinction, as it is

sometimes overlooked the fact that both theories are

incompatible. Either you are related to an ambiguous inner object

which happens to be projected onto a real person (object-relation

theory), or you distinctly know who you are related to, who you

are for the other party in the relationship, why you are related,

what you expect from the relationship in each interaction, and so

on.

BOWLBY'S CONTRADICTIONS

Let us examine Bowlby's contradictions regarding this central

arguments which approach personal relationships, psychology

and psychopathology in a radically new way.

In book 1 of his trilogy, Attachment, page 16, he asserts:

"Throughout this inquiry my frame of reference has been that of

psychoanalysis. There are several reasons for this. The first is

that my early thinking on the subject was inspired by

psychoanalytic work -my own and others'. A second is that,

despite limitations, psychoanalysis remains the most serviceable

and the most used of any present-day theory of psychopathology.

A third and most important, is that, whereas all the central

concepts of my schema -object-relations, separation anxiety,

mourning, defence, trauma, sensitive periods in early life -are the

stock-in-trade of psychoanalytic thinking, until recently they have

been given but scant attention by other behavioural disciplines".

So as we can see, he has a first sentimental reason to stick to

psychoanalysis, a second consensual reason, and a third

pedagogical reason. One wonders, what on earth did

psychoanalysis need Bowlby for to drum the practice away on

those three feeble grounds: nostalgia, hegemony, and an

example for other rebel stances (for instance, his own).

However, only seven pages later, he criticizes psychoanalysis'

way of gathering data for its conclusions. Psychoanalysis relies

on "a process of historical reconstruction based on data derived

from older subjects... "The point of views from which this work

starts is different... it is believed that observation of how a very

young child behaves towards his mother, both in her presence

and especially in her absence can contribute greatly to our

understanding of personal development. When removed from

mother by strangers, young children respond usually with great

intensity; and after reunion with her they show commonly either

heightened degree od separation anxiety or else unusual

detachment... Because this starting point differs so much from

the one to which psychoanalysts are accustomed, it may be

useful to specify it more precisely and to elaborate the reasons for

adopting it."

And he goes on: "Psychoanalytic theory is an attempt to explain

the functioning personality, in both its healthy and its pathological

aspects, in terms of ontogenesis. In creating this body of theory

not only Freud but virtually all subsequent analysts have worked

from an end-product backwards. Primary data are derived from

studying, in the analytic setting, a personality more or less

developed and already functioning more or less well; from those

data the attempt is made to reconstruct the phases of personality

that have preceded what is now seen."

"In many respects what is attempted here is the opposite. Using

as primary data observations of how very young children behave

in defined situations, an attempt is made to describe certain early

phases of personality functioning and, from them, to extrapolate

forwards. In particular, the aim is to describe certain patterns of

response that occur regularly in early childhood and thence, to

trace out how similar patterns of response are to be discerned in

later personality. The change in perspective is radical. It entails

taking as our starting point, not this or that symptom or syndrome

that is giving trouble, but an actual event or experience deemed

to be potentially pathogenic to the developing personality."

" Thus, whereas almost all present-day psychoanalytical theory

starts with a clinical syndrome or symptom -for example, stealing,

depression, or schizophrenia - and makes hypotheses about

events and processes which are thought to have contributed to its

development, the perspective adopted here starts with a class of

event -loss of mother-figure in infancy or early childhood- and

attempts thence to trace the psychological and

psychopathological processes that commonly result. It starts with

the traumatic experience and works prospectively."

It is fairly evident that an approach such as the one advanced

above cannot but clash against classical psychoanalytic mores.

Where psychoanalysis relies on memories, Attachment Theory

distrusts them. Where psychoanalysis asserts the natural site to

perform research is the consulting-room, Attachment Theory

declares research must be done out of psychotherapeutic

premises. Where psychoanalysis works retrospectively, trying to

reconstruct the patient's infancy, Attachment Theory is

determined to see by its own eyes what goes on during infancy

and early childhood directly, dispensing with untrustworthy

informants. But this is exactly what the "new generation" of

Attachment Theorists is encouraging throughout the United

States: Mary Main, Alan Sroufe, Pat Crittenden, Phil Shaver, Kim

Bartholomew, Charles Zeenah, Everett Waters, Hazan, Kobak,

Cassidy, Bretherton, Weiss, and so on, rely exclusively on

reports, self-reports: they interview a mother-to-be, or for that

matter, anybody else, and ask her about her relationship with her

mother. From her responses and the way they are made, they

infer the kind of early attachment the adult must have had with her

own real mother, as they are convinced patterns of attachment

endure unalterably throughout life. As to why they think all this

nonsense, we will elaborate on below. At any rate, I hope it is

crystal clear that present-day methodology amounts to about the

opposite to what Bowlby recommended half a century ago, and

which he had come to adopt as a rejection of similar methods

characteristic of psychoanalysis, a whole century ago. We

advance the argument that American Attachment Theorists have

harked back to psychoanalytic methods simply because it is far

less work, and much more popular. No parent likes to face the

sad reality of a distorted family context and severe alterations

within relationships, such as role-reversal (if you call it

overprotection, mother appears as loving and child facing a

lifetime task, that of cutting the umbilical cord with mother, which

is, of course, his entire responsibility), covert authoritarianism,x

outward permissiveness, perversions, physical, psychological and

sexual abuse, coaxing, everyday coercion, and so on.

But Bowlby is even more emphatic concerning the unreliability of

reports, let alone of self reports. On page 25 of Attachment and

Loss: Attachment, he says that psychoanalysts regard direct

observation of behaviour as superficial and that it contrasts

sharply with what is the almost direct access to physical

functioning that obtains during analysis. On page 26, he

unambiguously states: "Now I believe an attitude of this sort to be

based on fallacious premises. In the first place we must not

overrate the data we obtain in analytic sessions " (let alone data

obtained in interviews). So far from having direct access to

psychical processes, what confronts us is a complex web of free

associations, reports of past events, comments about the current

situation, and the patient's behaviour. In trying to understand

these diverse manifestations we inevitably select and arrange

them according to our preferred schema; and in trying to infer

what psychical processes may lie behind them we inevitably leave

the world of observation and enter the world of theory (i.e.,

speculation). As regards infants or children's observations he

firmly contends:" Since the capacity to restrict associated

behaviour increases with age, it is evident that the younger the

subject the more likely are his behaviour and his mental state to

be the two sides of a single coin. Provided observations are

skilled and detailed, therefore, a record of the behaviour of very

young children can be regarded as a useful index of their

concurrent mental state". As anybody can appreciate, nothing of

the kind is being carried out in the late nineties, where all that

seems to matter is adult attachment, and may God take care of

the kids. Furthermore, we can see from these quotations from

Bowlby's Attachment I, that reality takes pride of place over

fantasy, or inner representational models, which amounts to be

the same.

More differences between

the psychoanalytic approach

and that of Bowlby's

1. Ethology

In page 27 of his Attachment I, Bowlby says: "Another way in

which the approach adopted differs from traditional

psychoanalysis is that it draws heavily on observations of how

mothers of other species respond to similar situations of presence

or absence of mother; and that it makes use of the wide range of

new concepts that ethologists have developed to explain them."

"A main reason for valuing ethology is that it provides a wide

range of new concepts to try out in our theorizing. Many of them

are concerned with the formation of intimate social bonds -such

as those tying offspring to parents, parents to offspring (See my

Outline), and members of the two sexes to each other, and so on.

We now know that man has no monopoly either of conflict or of

behaviour pathology. A canary that first starts building its nest

when insufficient building material is available not only will

develop pathological nest-building behaviour but will persist in

such behaviour even when, later, suitable material can be at

hand.. Ethological data and concepts are therefore concerned

with phenomena at least comparable to those we as

psychotherapists try to understand in man".

2. Theories of motivation: Instincts

On page 34 of Attachment I, Bowlby continues: " Since the

theories that Freud advanced regarding drive and instinct are at

the heart of psychoanalytic metapsychology, whenever an analyst

departs from them it is apt to cause bewilderment and

consternation." The work of Rapaport and Gill (1959) provides a

useful point of reference.

In their attempt to state explicitly and systematically that body of

assumptions which constitutes psychoanalytic metapsychology,

Rapaport and Gill classify assumptions according to certain points

of view. They identify five such viewpoints, each of which requires

that whatever psychoanalytic explanation of a psychological

phenomenon is offered must include propositions of a certain

kind. The five viewpoints and the sort of propositions each

demands are held to be the following:

1. The Dynamic: this point of view demands propositions

concerning the psychological forces involved in a phenomenon; 2.

The Economic: This demands propositions concerning the

psychological energy involved in a phenomenon; 3. The

Structural: this demands propositions concerning the abiding

psychological configurations (structures) involved in a

phenomenon; 4. The Genetic: This demands propositions

concerning the psychological origin and development of a

phenomenon; and 5. The Adaptive: This demands propositions

concerning the relationship of a phenomenon to the environment.

Now there is no difficulty with the structural, the genetic, and the

adaptive. Propositions of a genetic and adaptive sort are found

throughout Bowlby's work; and, in any theory of defence, there

must be many of a structural kind. The points of view not adopted

by Bowlby are the dynamics and the economic. There are

therefore no propositions concerning psychological energy or

psychological forces; concepts such as conservation of energy,

entropy, direction and magnitude of force are all missing, because

of a model of the psychical apparatus that pictures behaviour as

a resultant of a hypothetical psychical energy that is seeking

discharge was adopted by Freud almost at the beginning of his

psychoanalytical work. "We assume," he wrote many years later

in the "Outline" as other natural sciences have led us to expect,

that in mental life some kind of energy is at work..." But the

energy conceived is of a sort different from the energy of physics

and consequently is termed by Freud "nervous or psychical

energy" (Standard Edition, 23, pp. 163-4)

Harking back to what had

been objected to:

Object-Relations Theory

- Working Models

It looks as though genial thinkers are also aware, too aware of the

scientific community social repercussions, and that it would put

them on the public placard of ridicule, were it the case, they were

proved wrong. As far as I know this has been going on since the

Inquisition times. Galilei had to backtrack officially lest he be

burned at the pire. Copernicus spends half of his book on "The

Revolutions of Celestial Spheres", trying to convince his pope that

his is but an instrumental hypothesis, concocted, not to displace

the EARTH from the centre of the universe, but an "as if" manner

to resort to more efficient predictions as to the positions of the

astral bodies, a fundamental issue for kings, princes and popes in

the wars they were engaged in. Examples abound in the history of

science: Lavoisier, Darwin, Freud, and now Bowlby.

Working Models, a mere change of terminology for "mental

representations" (See Bowlby's Scientific Stance)

Let us take a look at what he says in this respect on page 236 of

his Attachment II: Separation, under the heading of "Working

Models of Attachment Figures and Self":