|

The Sixteenth Century and Education

|

| The Sixteenth Century and Education

The Northern Renaissance and Reformation

Europeans of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries

experienced a complex of changes-economic, political, technological,

religious, scientific, aesthetic-which demanded a substantial increase in

the pool of leadership capacity. That, in turn, required enlarged

provisions for schooling and increased access to schools. ROYAL INJUNCTIONS Injunctions given by the Queen's Majesty, concerning both

the clergy and laity of this realm, published A.D. 1559, being the first

year of the reign of our Sovereign lady Queen Elizabeth. *** Xll. And, to the intent, that learned men may hereafter spring the more, for the execution of the premises, every parson, vicar, clerk, or beneficed man within this deanry having yearly to dispend in benefices and other promotions of the church £100, shall give £3. 6s. 8d. in exhibition to one scholar in either of the universities; and for as many £100 more as he may dispend, to so many scholars more shall give like exhibition in the University of Oxford or Cambridge, or some grammar-school, which, after they have profited in good learning, may be partners of their patrons cure and charge, as well in preaching, as otherwise in executing of their offices, or may, when time shall be, otherwise profit the commonweal with their counsel and wisdom. *** XXXIX. Item, that every schoolmaster and teacher shall teach the Grammar set forth by King Henry Vlll of noble memory, and continued in the time of King Edward Vl and none other. *** XL. Item, that no man shall take upon him to teach, but such as shall be allowed by the ordinary, and found meet as well for his learning and dexterity in teaching, as for sober and honest conversation, and also for right understanding of God's true religion. *** XLI. Item, that all teachers of children shall stir and move them to love and do reverence to God's true religion now truly set forth by public authority. *** XLII. Item, that they shall accustom their scholars reverently to learn such sentences of scripture, as shall be most expedient to induce them to all godliness. *** XLIII. Item, forasmuch as in these latter days many have been made priests, being children, and otherwise utterly unlearned, so that they could read ne say mattens or mass; the ordinaries shall not admit any such to any cure or spiritual function. * * * England: rhetoric and education

[The following accounts of Luther and Loyola were

prepared by Byron Stevens, graduate assistant in Educational Policy and

Administration during 1996-98. Sources used included Benet's Reader's

Encyclopedia (3rd ed.)] -Byron Stevens, 1998 * * * SELECTIVE LIST OF SIXTEENTH-CENTURY FIGURES IN EDUCATION The growing interest in education that was part of

Renaissance and Reformation movements resulted in an increasing number of

individuals making their voices heard on the subject. An inspection of

textbook indices can be daunting for the uninitiated-all those names! In

addition to the Protestant and Catholic leaders noted above, the list

below includes some of the best known figures active in sixteenth-century

educational theory and practice. |

| Europe and

England Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536, Dutch, Rotterdam). Humanist. Editor of classic Greek and Latin texts. Prolific author of works on education, e.g., Education of a Christian Knight, The Right Method of Instruction, The Liberal Education of Boys, Colloqies, and many more. | |

Juan Luis Vives (1492-1540, Sp., Valencia) Writer. Tutor of Princess Mary Tudor, 1523.

France

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592, Fr. Dordogne). Landed gentleman. Mayor

of

Bordeaux.

Peter Ramus (1515-1572, Pierre de la Ramée, Fr. ). Author of many texts. First professor of mathematics at the Royal College of France.

England

Thomas Elyot (1490-1546, Eng.). Knight.

Richard Mulcaster (1548-1611, Eng.). Schoolmaster.

Scheduled reading | |

| SLIDE LIST SIX Reformation Education | |

| Human nature and education | |

| 1. | Chart of man and nature, a woodcut in Bovillus, Liber de intellectu (1509). |

| Emblem books | |

| 2. | Studiis invigilandum. [Careful study.] Geoffrey Whitney. A Choice of Emblems. Leyden, 1586. |

| 3. | Praecocia non diuturna. [Precocity does not last.] Ibid. |

| 4. | Scripta non temere edenda. [Don't publish careless writing.] Ibid. |

| 5. | Usus libri, non lectio predentes facit. Ibid. |

| 6. | Habet ut bellum suas leges. [Laws of war.] Ibid. |

| Study space | |

| 7. | Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam, ca. 1523 by Hans Holbein, the Younger. Louvre. |

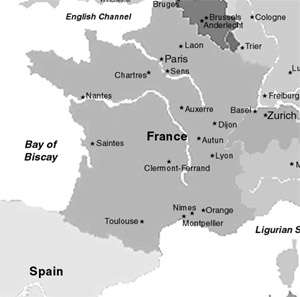

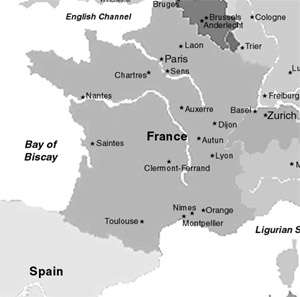

| 8. | Photo of reconstruction of Erasmus' study. Anderlecht, within the Brussels complex. |

| 9. | Woman in her study. Eng. manuscript painting, 16th c. |

| Mother as teacher: St. Anne and St. Mary | |

| 10. | St. Anne and Virgin, reading lesson. Terra cotta, Fr., end of 16th c. Paris, Tokyo Museum. |

| 11. | St. Anne and Virgin, reading lesson. Sculpture, Fr., 1st half of 16th c. London, V&A. |

| 12. | As above, side view. |

| 13. | Madonna and Jesus, reading lesson. Marble, north Ital., 16th c. Liverpool, Walker Gallery. |

| Grandmother in family and

education: St. Anne, her children and theirs | |

| 14. | Heilige Sippe. Altar piece painting. 1505. Ger. Frankfurt Municipal Museum. |

| 15. | Holy Kinship. Tapestry. 16th c. Ger. Dom treasury. Mainz. |

| 16. | Holy Kinship. Painting. 1562. Neth. |

| Reformation in Germany: the Preceptor | |

| 17. | Nuremberg. View. |

| 18. | Nuremberg. Tower. |

| 19. | Melancthon. Statue. Stands before the Nuremberg central grammar school and main public library. |

| 20.-21. | Details. |

| Skeptical humanism | |

| 22. | Montaigne. Sic transit gloria mundi. |

| 23. | Detail. |

| Entrepreneurial secular schools: profit and virtue | |

| 24. | Schoolmaster's sign, 1516. Ambrosius Holbein. Basel City Museum. |

| 25.-26. | Details. |

| 27. | Temperance, 1559, print from a series on the virtues, by Pieter Bruegel, the Elder. |

| 28. | Detail. |

| 29. | Schoolmaster and student, marginal drawing by Hans Holbein, for Erasmus' The Praise of Folly. |

| Some 16th century grammar schools | |

| 30. | Stamford town grammar school. |

| 31. | Another view. |

| 32. | Shrewsbury grammar school, 1552. |

| 33. | Detail. |

| 34.-36. | Stratford on Avon grammar school. |

| 37.-54. | Westminster Abbey and School. London. |

| 55.-57. | Winchester. |

| 58.-60. | Eton. |

| 61. | St. Paul's. |

| 62.-64. | Rugby. |

| 65.-67. | Christ's Hospital. |

| 68.-71. | Lycée Fermat. Toulouse, Fr. |

| Satire and Reformation schooling | |

| 72. | "The Ass at School," 1556, by Pieter Bruegel, the Elder. |

| 73. | Detail. |

| 74. | "Ala Mode School," print by Pierre Bailleu. |

| 75. | Detail. |

| Concurrency of Reformation and Renaissance themes | |

| 76. | Instruction of Cupid in Architecture. Bronze, 16th c., A. Leopardi (d. 1523) London: V&A. |

| Ancients and moderns on a par | |

| 77. | "The School of Athens," fresco, 1515/11, Raphael Sanzio. Stanza della Segnatura, Vatican. |

| 78. | Detail. Archimedes or Euclid. |

| 79. | Detail. Zoroaster, Ptolemy, Raphael, Sodoma. |

| 80. | Detail. Michaelangelo. |

| Questions for Study and Discussion | |

| 1. | What reasons explain why Protestant reformers, such as Luther, Calvin, Zwingli, Knox, emphasized elementary-level schooling for all? |

| 2. | Imagery of Jesus at school became rare in the sixteenth century. Why? Did Jesus-at-school imagery provide a positive model for Christian children? |

| 3. | If Peter Bruegel's "The Ass at School" is viewed in relation to Reformation movements, what symbolic meanings emerge? What is your understanding of the caption beneath Bruegel's print [You can send an Ass to Paris to learn, but he won't come back as a horse]? |

| 4. | The idea of teaching Cupid to read traces to at least Roman antiquity. It recurs in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. What is your understanding of the theme and its imagery? |

| 5. | Among compositions expressive of education themes, "study space" is depicted frequently. What is the usual character of study space? What would you not expect to see in sixteenth-century representations of study space? |

| 6. | Increased state interest in education was among the distinguishing features of the Reformation, according to textbooks on the history of education. What evidence do you find to support or negate this textbook generalization when you look into the passages from the Royal Injunctions quoted above? In what specific ways, if at all, do the Injunctions indicate interest in controlling who shall be schooled, by whom, by what means, to what ends? |

| 7. | During the years preceding the Reformation-or the "Protestants' Revolt," depending upon the interpreter's perspective-the Waldenses, Brethren, and other dissenters from the established Church began to use a catechism first printed in 1498. This little book was based on St. Augustine's Enchiridion. Catechisms proliferated during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As popularly understood in the twentieth century, catechism refers to a form of instruction mainly for children, although it was used with children and adults alike in civilized antiquity, the schools of Judaism, and the early Christian church, and was so used again during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. What is the catechetical form of instruction? How does it differ from dialogic forms of teaching and learning? Luther had preached a direct relationship between persons and the deity and that people should read the Bible for themselves, yet by 1529 he had produced catechisms, as did John Calvin in 1537, and so did many other churchmen and church councils. What would have motivated the production of catechisms? |

| 8. | Jesuit schools, which were among the developments referred to as the "Counter-Reformation," attracted the admiration even of those who were not sympathetic to the Society of Jesus. What was it about these schools that brought them high regard? |

| 9. | To test claims purporting to explain high levels of rhetorical artistry in a period such as the Elizabethan age, what would you wish to know about social conditions generally? About education and schooling? |

| 10. | Early modern textbooks in grammar and rhetoric usually include sample sentences. How might a "content analysis" approach to these texts shed light on contemporary interests, attitudes, or values? Looking to the selections from Peacham's Garden of Eloquence (1577) quoted above, what indications do you find, if any, revealing assumptions about what it means to be "educated"? About subjects worth studying? About the proper scope of learning? About proper attitudes toward well educated people? |

| 11. | The status of vernacular languages rose during the sixteenth century in Europe, especially Northern Europe. More books were translated from Latin into local languages. More people began to read in the "language of the mother's knee." What explains these increases? Religion? Nationalism? Something else? If so, what? |

| 12. | What bearing, if any, does the European exploration of the "New World" have on education in the sixteenth century? |

| 13. | "Emblem books," a special kind of printed book invented in the early 1530s, became increasingly popular as the century wore on, with popularity continuing to increase in the seventeenth century. What is your understanding of this literature, which is sometimes called a "para-literature"? Why should it have become, according to its historians, a source of popular moral education during the early modern era second only to the Bible? |

| 14. | Montaigne's Essays, which first appeared in the 1580s, may be understood as contributing not only to the history of literature but also to the history of educational thought. In what sense might the essay be a contribution to thought about education? |

| Women's Education, 16th century: Selective Bibliography | |

| Bayne, Diane Valeri. "The Instruction of a

Christian Woman: Richard Hyrde and the Thomas More Circle," Moreana 45

(1975), 5-15. | |

| Hull, Suzanne W. Chaste, Silent and Obedient:

English Books for Woman, 1475-1640. San Marino: Huntington Library, 1982.

[820.9H877] | |

| Irwin, Joyce. Womanhood in Radical

Protestantism, 1525-1675. N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press, 1979.

[BT704.I78] | |

| Kaufman, Gloria. "Juan Louis Vives on the

Education of Women," Signs 3/4 (Summer 1978), 891-896. | |

| Sowards, J. K. "Erasmus and the Education of

Women," Sixteenth Century Journal XIII/4 (Winter 1982), 77-89. | |

| Wiesner, Merry A. Women in the Sixteenth Century: A Bibliography. St.Louis, MO: St. Louis Center for Reformation Research, 1983. [Wilson ref. HQ1148.W53x | |

Continue With Course Units: The Seventeenth Century and Education